Reflecting on my tenure at the City of Boston

Featured Content

This post was featured in The Analytics Engineering Roundup weekly newsletter on April 28, 2024.

Thank you Jason Ganz for the shoutout!

March 1st, 2024, was my last day working as a data engineer on the City of Boston Analytics Team. For the past month or so, I’ve been taking some time to reflect, and appreciate just how much I have learned and accomplished during my 2-year tenure at City Hall. This blog post is an attempt to document my growth - and also provide an outlet for the thoughts that have been bouncing around in my brain. So while I do want to let any curious readers know what my journey was like kicking off my career as a mission-driven data engineer, I also reserve the right to meander a bit.

While I did a couple shorter-term independent contracting gigs between earning my degree and working for the City, I consider my role as a data engineer on the City of Boston Analytics Team as my first “real” data job - first time working with a data warehouse, first time working collaboratively with other data engineers (and first time creating & reviewing Pull Requests), first time creating production ETL pipelines with an orchestration platform (and maintaining workflows & pipelines other people created)… all of the firsts that come with working as a part of larger data team rather than completing an entire data project by myself. And besides giving me the opportunity to kickstart my career as a data engineer, working for the City also solidified my passion for civic tech. Knowing that my daily work is directly tied to a mission of improving people’s lives is a significant motivator for me - and that will continue to shape the choices I make in my career.

Looking back, I can divide my tenure into 2 halves:

(1) the first year, during which I learned how to become an effective data engineer on the Analytics team - learning the tools, processes, and standard practices; and

(2) the second year, during which I was able to implement improvements to our tools, processes, and standard practices - and ended up re-architecting our data warehouse & ELT pipelines along the way.

So, let’s meander in (mostly) chronological order.

tl;dr

Maybe you don’t feel like going on a journey with me at the moment, and you just want the highlights - this section is just for you.

What I learned:

- How to work with data warehouses (ELT, workflow orchestration, flow of transformations, testing the data, etc)

- Patterns of collaboration & communication with fellow engineers (e.g. PR flow & etiquette, documenting work), analysts (e.g. division of responsibilities, data modeling), and stakeholders (e.g. requirements gathering, advocating for data engineering best practices)

- The formal process of process improvement - how to develop and communicate innovative projects that will improve daily processes

- How to start a dbt project from scratch and iteratively grow its architecture & adoption

- How to present a fairly technical data engineering process improvement project to teammates, leadership, and a wider audience

What I accomplished:

- Starting & growing the City Analytics Exchange, a casual network & meetup group of data analytics practitioners in local government

- Teaching workshops (from Software Carpentries) on core technical skills like git, SQL, and python to fellow City employees (part of a larger data culture initiative)

- Integrating dbt into the data engineering team’s tech stack, and re-organizing the data warehouse along the way

- Presenting about the dbt migration project at Coalesce 2023

- Collaborating across many teams & individuals in the department to deliver the team’s first data catalog as an official product supported by the department (SSO, boston.gov URL, data governance work initiated to support continued development)

Links to look at next:

- Blog post: Analytical Data Warehouses - an introduction

- Project page: dbt Migration at City of Boston

The first year (aka the year of learning)

When I came into this role, I had no prior experience working with a data warehouse, but a decent amount of experience working with databases. For me, learning to work with an analytical data warehouse was a paradigm shift - I had the core technical skills, but it felt like the conceptual foundation I had built on how to work with databases turned to sand beneath my feet.

As a student, I had learned how to design for and query normalized transactional databases. It had become second nature for me to understand new data by putting it into 3rd Normal Form, and implementing strong constraints on a database was a given. Have messy data? Design a relational model, then clean and wrangle the data into shape using python to output normalized, tidy tables that could then be visualized and analyzed. This was all fine for independent data projects, but it meant that I didn’t even realize I would need a whole new way of conceptualizing data work once I started working on a data team with a data warehouse. The first few months were a shock to the system!

I think there were two pivotal things that helped me adjust and reframe how to work with data in a more collaborative ecosystem: (1) taking the month-long synchronous online course “Analytics Engineering with dbt” from CoRise, taught by Emily Hawkins and Jake Hannan, and (2) staying connected with and learning from the data community online via social media. The combination of actively learning in more of a “classroom” environment, observing and absorbing data professionals talking about their work in a public online forum, and then being able to see how those learnings applied during my daily work at the City, all together had the effect of accelerating and supercharging my learning and re-orienting process. I was able to construct a new conceptual foundation for working with analytical data warehouses within a relatively short time, and then I could continue to iterate and build on that new foundation.

I owe a lot of thanks to Emily and Jake for answering my questions and having conversations with me during the CoRise course as I was building my conceptual foundation - those conversations and the resources they pointed me to were really helpful! I took the CoRise course in February/March, less than a month after starting at the City.

Before taking the course, all I knew was that dbt was popular in the industry and I should probably learn it. It was a very happy coincidence that I had signed up for the dbt CoRise course a while before even starting at the City - I had been hearing about dbt online but didn’t really understand what it was for. It took my brother convincing me over Thanksgiving vacation that if I wanted to work on a data analytics team I really needed to learn dbt, even if I didn’t know what exactly it was used for. So for the sake of “professional development”, I signed up for the CoRise course in hopes that I could at least learn what was even the point of this new tool everyone in the data community was so enamoured of.

After the course, not only did I understand what dbt was, but I understood why it was so valuable when working with a data warehouse… and how it could help improve the data engineering team’s workflows. It took about a year to get to the point of even starting that journey, but the seed was planted pretty early on.

While my knowledge about databases and data modeling has grown a lot over the past couple years, I have still held on to a few biases due to my roots in 3NF. First, I still think that the best thing you can do with messy source data is to normalize it. A normalized relational data model provides a strong and flexible foundation that can be queried and transformed into whatever shape you need it to be next. Second, primary keys are essential. Foreign keys and check constraints may be exceedingly rare in a data warehouse, but primary keys are the one contraint that will always be useful. The idea of primary keys being “unenforceable” and “just for documentation” gives me the heebie-jeebies. I understand why (performance), I just don’t like it.

On the flip side, there are some biases I started with that I have done a complete 180 on. When I first started as a data engineer, I wanted to do everything in python. I was very comfortable with pandas, and you could do much more complicated data transformations in a python script, so I thought that python was the best choice. Now I know that SQL is king - if you can keep it in the database and do the transformation in a SQL query, don’t even think about using python. Also, there’s no need to jump straight from source data to the final dataset in one long, complicated transformation when you can also get there with a few more steps that are simpler and modular - some of those smaller transformation steps may be re-used for other purposes. Finally, there is no single correct way to format/model your data - there are many different possible ways, and the best choice is the one that will actually get used (which is pretty much never the normalized version).

I think my overall point here is this: I was able to go from not really understanding what a data warehouse was to having a good enough understanding of them to re-architect the team’s warehouse and the ELT pipelines powering it inside of 2 years. But that learning journey was rather rocky, and the first few months were especially tough given the lack of formal training. Reflecting on that experience - both how much I had learned by doing & researching on my own, and imagining how that learning process could be smoother for myself and others - was the driving motivator for me writing the introduction to analytical data warehouses blog post (now turning into a series). In fact, that blog post started as a page in the team’s internal documentation that I decided to generalize and expand on, in case other folks might find it useful. I spent a lot of time and brain power on truly grokking the data warehouse from scratch, and that is something that I am both proud of and hope others don’t have to go through alone (though many inevitably will).

One final reflection on this: I realized that the reason I did not initially understand the point of dbt was because I didn’t understand data warehouses and how to work with them. dbt solves a specific problem that every team working with a data warehouse experiences, and it solves it very well, which is why it is very popular within the specific community of data practitioners who work with data warehouses. Once I understood how to work with a data warehouse (compared to a database), understanding the value proposition of dbt and how to use it was much easier. Figuring out how to use dbt within our specific data warehouse… that was something my brain started noodling on endlessly towards the end of year one.

City Analytics Exchange

I mentioned that another important part of my learning process was being connected to the larger data community online, and this perspective was one of the primary motivations behind my City Analytics Exchange initiative.

As a member of the City of Boston Analytics Team, I didn’t just want to learn from my fellow Boston teammates - I also wanted to learn from data analytics practitioners in other city governments. Fortunately I was not alone, and other teammates also wanted to cultivate a network of city analytics professionals! We started by reaching out to former teammates who had moved on to work for other cities, who could then reach out to their new teammates. We also started with a couple of motivating topics - specific tools that we all used or initiatives we were all trying to work on (e.g. knack, open data portals).

I created a free Slack workspace so we had a shared space to communicate, and scheduled time to (remotely) meetup with a loose agenda. We had a goal of meeting roughly once a quarter, and adding 1 new city each time we met. With an existing communication and meeting structure, it was much easier to add new folks each time we talked to other city data teams for some unrelated project - and surprise, suprise, other city analytics folks also wanted to talk to professionals doing the same kind of civic tech work! We got to share our accomplishments, work through problems, and generally collaborate, commiserate, and cross-pollinate in a casual environment of individual contributors doing hands-on-keyboard work.

I’m happy to say that the City Analytics Exchange is still going strong, and other members have stepped up to help facilitate the community moving forward. I hope that it continues to grow and be a resource for city data workers. If you are on a city analytics team and want to join, you can reach out to Amy Hood or Sam Firke.

The process of process improvement

Early in 2023 the Analytics Team collectively took the “Advanced Innovation Training” with Brian Elms from Change Agents Training. We learned about techniques like process mapping & identifying waste, standard work and systems of work, batching vs flow, nudging, and how to calculate the value of innovations/improvements. We teamed up and developed some innovations that we could implement for the Analytics Team (although… most of these never actually happened). Many of the techniques seemed simple or obvious, but I think in large part the specific techniques or toy improvement projects were only the delivery mechanism: the real value was in initiating and enabling a culture shift so individual contributors (rather than managers) could feel empowered to make small (or large) changes to how the team got things done (a.k.a improving processes)… and then have a framework for proposing/communicating these innovations to both teammates and leadership.

In the 2nd half of 2023 two dedicated process improvement coaches (Kayleigh and Nolan) joined the Analytics Team and started to build out training for Boston city workers, and my understanding of the practice was able to advance even further through conversations with them.

The primary reason I wanted to highlight this training and what I learned from it, though, is that you could argue that the dbt migration project I kicked off in year 2 was just one very long process improvement project. I was an individual contributor, not a manager, but I was still able to propose and implement an improvement that would substantially change how the team worked with the data warehouse. I had essentially spent a year constructing an internal process map of how the data warehouse functioned, and I could identify many instances of how implementing dbt would reduce waste in that process. I could use the tools and techniques I learned in the Innovation Training course to communicate the value of spending time implementing dbt to leadership and others who weren’t familiar with the daily work and processes the data engineers and analysts followed.

What a perfect segue into…

The second year (aka the year of doing)

Starting around December 2022, I started to think more seriously about how the data engineering team could start to use dbt. There were three main obstacles I had to overcome: (1) I had to show that dbt would provide a real value-add and would be worth the investment of time and resources so that it could evolve beyond a personal pet project into something the entire team could work on, (2) I needed to get all of the setup figured out so it would be as easy as possible for the second (and third, etc) engineer to start contributing to the project, and (3) I had to decide whether to make dbt fit the team’s current data warehouse architecture, or whether and how to redesign the data warehouse.

I also had a couple of theories in how to overcome these obstacles: (1) the dbt-generated docs site with its clean documentation and pretty lineage graphs would be the biggest selling point of dbt, and (2) the easiest path in getting started would be to work outside of the existing data warehouse in a small separate database using open data with a complex lineage graph. I also hadn’t yet decided on the best path for obstacle #3, and pursuing a toy example that could demonstrate the power of the docs site would buy me some time to think through possible solutions.

Thus began a solid few months of what felt like banging my head against a wall in hopes that answers would fall out. I’m not going to lie - it was rough. It didn’t help that the open data set with a complicated lineage I had chosen, CityScore, hadn’t been maintained and was a much bigger beast than I was anticipating. It was essentially a practice run that never fully materialized - I struggled through figuring out how to set up the infrastructure needed to develop and run a dbt core project locally, and hacked away at how to refactor the CityScore pipeline into a set of dbt models. Even though I never reached my target shareable end product for that toy project, I did learn a lot along the way. It gave me time and the opportunity to clarify my thinking and approach in how to migrate our transformations to dbt in the real data warehouse.

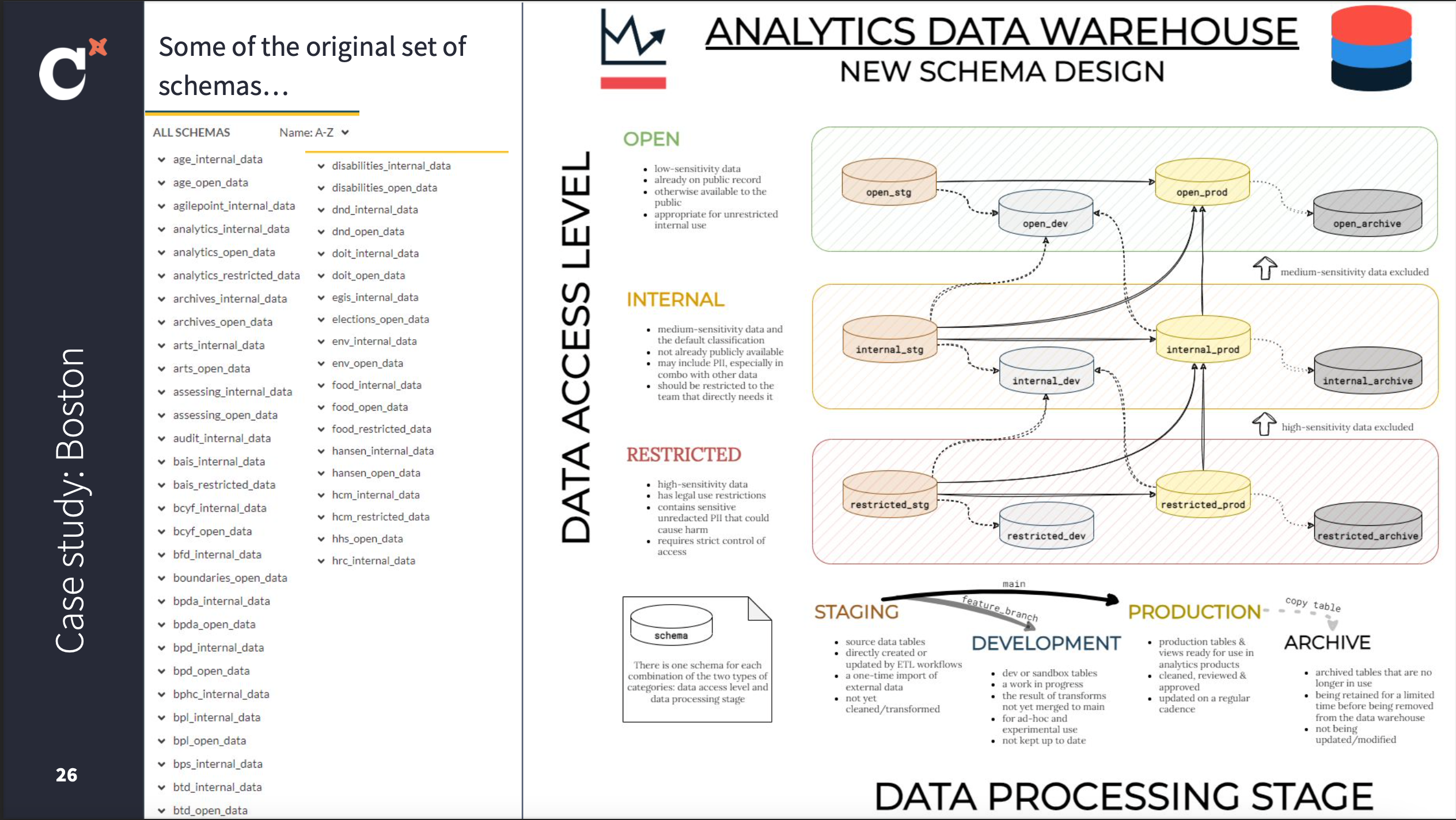

Along the way I decided on how to solve obstacle #3: the best approach would be to redesign the data warehouse with a new set of schemas that were designed with dbt in mind. With the dbt work isolated to an entirely new set of schemas, that new experimental work could proceed without interrupting the existing data & pipelines. We would essentially be slowly duplicating our existing workflows and data, but in a different set of schemas, with all transformations and tests living in dbt, and the import and export tasks re-organized around the dbt transformations.

FYI

If you just want to find the City of Boston dbt project details/links/resources (such as the above presentation), head on over to the project page.

If you want to hear some of the back story on how it all happened, you can keep reading this post.

Redesigning the data warehouse was not a decision I could make in isolation, of course - this was a decision that would effect the entire Analytics team, as well as anybody else who was using the data warehouse. It was also a change that had to stand on its own merits - while the new set of schemas were designed with dbt in mind, simply facilitating a migration to dbt would not be a good enough argument for making such a substantial change. Fortunately, others had been feeling the pain of our existing schema organization as well, and the new set of schemas solved many of these issues: (1) isolating the source/staging layer from “production” tables & views, (2) substantially fewer schemas, (3) eliminating the need to create new schemas every time a new dataset was added that didn’t fit into any of the existing schemas.

The old set of schemas were organized along the 2 dimensions of access level (open, internal, restricted) and data owner (department, team, source system, etc). The new set of schemas preserved the access level distinction, but instead of also organizing by data owner (the reason there were so many schemas), they were organized by data processing stage (staging, development, production). The addition of a “development environment” in the data warehouse was also a huge selling point for the engineers - previously, everything was production.

After getting approval from leadership, I presented this proposal for a new set of schemas to the team in March 2023. I wrote up a long document detailing why the old set of schemas were problematic, why the new set of schemas were organized this way, and how this would change some of our ways of working. I also created a form so that the entire team would have a chance to vote and give input on the new set of schema names - prod vs production vs mart? open_prod vs prod_open? staging vs stg vs source? Overall, the feedback was positive and many people gave their input on the new schema names. And while dbt was mentioned as a next step, the decision to adopt the new schemas was made entirely on its own merits.

With the team’s approval and a new set of empty schemas, I could move forward with the next step: actually getting the real dbt project up and running. Fortunately, I had learned a lot during my experiments over the past few months, so I already had a rough plan of approach. The biggest hurdle would be getting the first model to successfully run - not only being able to run a dbt command on my local computer to query and create a table, but also creating a workflow in Civis that would run a dbt command within a docker container and successfully connect to the database and create that table. And the local development environment needed to be sufficiently documented and easy to setup so that other engineers could do the same thing. Getting both the development environment (VS Code + dbt power user extension, venv, environment variables + profile for database connection) and the production environment (docker container, Civis credentials + environment variables for database connection, Civis workflow) correctly set up took some trial and error, but eventually we figured it out and got it running. By May 2023 the dbt project repo, local development environment configurations, and production civis workflow were all set up and there were a few models added to serve as examples. None of this would have been possible without the support of Albert Lee, our AWS/Docker/all-things-infrastructure wizard.

The next steps were to start populating the staging schemas with the most frequently used core sources (e.g. the 311 database, the permitting/licensing database, the EGIS database) and migrating over transformations that used those data sources, as well as onboarding the engineers most excited to start working on the dbt project. Going from 1 to 2+ people working on the project is always a big but important step, and was a good opportunity to work through any kinks in the process (is the documentation thorough enough? does it work on your machine?). By June 2023 there were 3 of us working on the project, and we were able to ramp up the migration process. I’m so grateful to Jenna Flanagan and David Falta for their strong and early belief in the dbt project (and their continued commitment to it after my departure!).

By July most of the engineering team had been onboarded to the dbt project, and we also had a very good idea of what to focus on migrating in the near term. In addition to the new schemas and dbt migration on the data engineering side, the analysts were starting a migration project of their own - transitioning from Tableau to Power BI. The timing for this double migration worked out perfectly, and we decided that all Power BI dashboards would be built exclusively from the new production schemas (and thus the transformations being handled by dbt). Once the set of dashboards being rebuilt first were determined, the engineering team had a definite list of table dependencies to focus on migrating to dbt and the new schemas. We could also go ahead and document those future dashboards and their dependencies as exposures in the dbt project. And given that the dbt generated documentation site was the initial selling point of dbt (those lineage graphs!), we also focused on getting an internal website (hosted via AWS services) that was updated daily ready for the team to reference.

By September we had successfully migrated all of the high priority Power BI dashboard dependencies, had a hosted dbt-generated documentation site customized with City of Boston branding, and the new set of ELT workflows (the new import workflows and the dbt build workflows) were running daily in production. Within 6 months we had a functioning (if minimal) redesigned data warehouse and dbt-centric ELT workflows… just in time.

Presenting our work in public at Coalesce

I just sketched out the work we were able to do in 6 months, but let me go back in time to the start. In March, before actually doing any of the work but after getting the go-ahead from the team, I submitted a talk proposal to Coalesce, the yearly dbt user conference hosted by dbt Labs. When I looked for other organizations using dbt, I saw a lot of companies - startups and large corporations - but nothing from government or other public sector adjacent organizations. But I knew that there had to be some other public sector data professionals using dbt, and after reaching out to a few folks in my network I found out that the State of California’s Office of Data & Innovation team was also using dbt. Not only that, but Ian Rose, a senior data engineer on the team, would be willing to join me in proposing a talk for Coalesce! I was so happy and grateful that I would not have to submit a talk alone (public speaking is scary! … and I’d never given a conference talk before!), and I knew that with more examples we could present a stronger case to other government data teams that they, too, should consider using dbt.

We submitted the talk proposal in March, not too long after I typed “dbt init” for the official project. Coalesce was happening in October. So I knew that I had 6 months to not only get the dbt project into a reasonably presentable state, learn as much as I could on both the socio- and -technical side of managing this migration, and also figure out what exactly we wanted to say during our 30 minutes on stage. In June we learned that the talk had been accepted, and in July after announcing the talk we were able to add another cospeaker who had been working on a dbt project in the public sector, Laurie Merrell. You can imagine my relief at achieving an MVP (minimum viable project) by September! But while the technical sprint was slowing down, the social sprint was just starting. Presentations have a way of spawning more presentations (not to mention the accompanying practice presentations). So along with working on our official Coalesce talk with Ian and Laurie, I was also crafting presentations for the Analytics Team, the CIO (head of the department), and the department at large. On the one hand, I wanted to make sure everyone at my workplace would be very familiar with the material I would be presenting in public (a presentation that would also be recorded and posted on the internet), and have the chance to provide any feedback/input. On the other hand, I really needed practice presenting this material! The marathon of presentations (and their practice sessions) leading up to Coalesce definitely helped me be more prepared in San Diego.

Attending Coalesce was one of my favorite experiences of 2023. The community of data practitioners that gathers at Coalesce is truly amazing - the online friends I had not yet met in person (including my cospeakers!) and the new friends I was able to meet through the talks and social events, the impressive speakers sharing their work, the professional support networks (Data Angels!), even the dbt Labs folks who had been providing me assistance via slack… the people are the reason why I want to go back and attend Coalesce next year (and the year after that!). I’m not going to into too much detail about my experience at Coalesce, because (1) this post is already too long and (2) I was posting my observations and reflections the week of on LinkedIn, but suffice to say that I was very grateful that our presentation was on the first day so I could devote the rest of my time to just enjoying the conference. Oh, and I also got a cool certification after passing a test within an hour of arriving at the hotel ;)

Fun fact: I had an early flight and had not yet eaten before arriving at the hotel in San Diego, so after finding the exam room I grabbed an acai bowl to eat during the test (the closest place to buy food was a frozen yogurt place and acai bowls are delicious) that may be owed partial credit for me passing and becoming a certified dbt developer. The test itself is mostly a blur but I have vivid memories of that acai bowl.

Product(ion)izing the Data Catalog

Delivering the presentations about dbt to others in the department ended up being extremely useful for the next phase of the dbt migration as well: publishing the dbt-generated documentation site as an officially supported product, with a boston.gov URL and Single Sign-On access. While the engineering team alone was sufficient to migrate the transformations and tests over to the dbt project, many more teams and leaders in the department would need to contribute their time and effort to help turn the documentation site into an officially supported product. This effort was kicked off in November, with the majority of the work allocated for the following quarter (January - March).

Alejandro Jimenez Jaramillo, the department’s inaugural Director of Tech Governance and Policy, immediately saw the utility of an official data catalog in advancing data governance efforts. Aleja and I had worked together on data governance issues when they were a fellow in 2022, and after they rejoined the department in 2023 we were able to continue that data governance work through the data catalog. Without Aleja and others in the department, the data catalog project may have never gotten off the ground. But because of their efforts, and collaboration across many teams in the department, the first phase of the official data catalog was launched and available by my final day. Logging in to datacatalog.boston.gov before losing access to my Boston accounts was the best goodbye gift I could ask for.

Iteration is the root of progress

The first six months of the dbt project (March - September) were devoted to getting a minimum viable project up and running, with the first set of tables needed for high priority Power BI dashboards reliably updating in the new set of schemas. The next six months (October - March) were primarily about getting the rest of the workflows (imports, transformations, tests, exports) migrated, but it was also about iteratively improving our implementation of dbt. With all engineers now comfortable with the essential dbt skills, some were able to dive deeper into specific features in order to improve our usage of them and the overall dbt project.

When I presented about the City of Boston’s dbt project at Coalesce, I also published a skeleton version of our dbt project repository in a public repo. Before my last day, I updated this repo to be in line with our implementation as of March 2024. So, you can easily compare what changes were made over those 6 months. While this does not represent all of our improvements (so, anything that is implemented only in individual model sql/yaml files is not captured), it does capture most of them. I may write another post in the future outlining all of the key features we added that I think should be part of any dbt project (let me know if there’s any interest in that!).

I’m so proud of the progress our team made, and by the time I left in March the migration was about 75% complete and I was fully confident that the team could continue the dbt project work and migration without me - as well as carrying forward the data catalog and data governance work. There were a few key things that I think contributed to the project’s success as a team-wide initiative, rather than just being my personal project (which would not have had a lasting impact!):

- We set aside time for a weekly dbt sync, where all of the engineers could meet and discuss the status of the migration, propose features and improvements, ask questions to improve their own understanding, and share their own learnings and discoveries. The meetings were half project management and half knowledge sharing, and I was very intentional in making sure they were a collaborative, safe, and open environment. We were all learning and developing this project together. We also traded off facilitation roles so that there was not just one person in charge of the meeting.

- We made the right things the easiest things. For example, we wanted to make sure that it would be very easy to add documentation to models at a later point - possibly by those less familiar with dbt. So, every model SQL file also had a YAML file with description fields for every column. Through a combination of the codegen dbt package, some custom macros, and bash scripts, it was as easy as specifying the access level and a model name as arguments and running a bash script to create the base YAML and SQL files. It was fast, easy, and accurate.

- I put a lot of thought into the initial design, and made sure that the database design and dbt project design worked together cohesively. And once that larger design was decided, we stuck to it. This consistency in the overall design and architecture of the project meant we could focus on the smaller implementation details, and be confident that the ground would not move beneath us as we were trying to build on it.

- We collaboratively developed a “style guide” and standards for our work in the dbt project. Much of this borrowed from the official dbt Labs recommendations (e.g. keeping the source and ref macros at the top in a “model imports” section, having 1 SQL and 1 YAML file per model), and some of it was customized for our project (e.g. using the generate_geom_column macro for all geometry transforms, and making sure every source had the custom table-level test test_table_not_empty). We held each other to these standards in PRs, and could raise any questions in the weekly syncs.

- We didn’t try to do everything at once, and perfectly for the first time. Instead, we focused on the next thing that needed to happen given the team’s goals and current priorities. That means that there are some things we had not implemented by March that many data teams might consider essential (like CI/CD checks & pipelines), and others things we implemented relatively early that many teams may not consider as important (like custom styling for the dbt docs site). When we had a relatively small number of models, we didn’t focus on optimizing when those models ran. But when we had many sources and were moving more to be updated at night (and the database was overloaded during the morning run) it became important to implement the freshness selector for the nighttime and morning dbt builds. When a migration happens on top of your regular workload, you quickly learn to prioritize only what is absolutely needed next - and having a vision for the future state can help a lot with that more immediate prioritization.

None of this is to say that our migration went perfectly smoothly - we ran into plenty of hiccups and challenges along the way. For over a week our postgres database ran out of memory and crashed every morning at about 9am (right when it was needed for dashboard refreshes). Analysts suddenly lost the permission to query tables they needed. Some models that should be part of the daily run were not included, so some tables had stale data and we didn’t catch it until a stakeholder raised the issue. We were all learning how to build the airplane as we were building the airplane as we were flying it - and because we had a talented and dedicated team of engineers we did eventually diagnose and solve these issues… and we all learned so much in the process!

I’m so excited to see what the team does next with the dbt project. My goal/hope is that the analysts join the engineers in contributing to the dbt project repo. Maybe data owners will start contributing documentation to the data catalog. Analysts may start using dbt metrics (maybe even the semantic layer!) in pursuit of a standardized city-wide metric library. Perhaps in a few years, other data teams throughout the City will develop their own dbt projects, and a multi-project dbt mesh could be established. With the dbt project established, other tools from the modern data stack (those with open source options, of course) could be added to the data engineering team’s toolbox.

In order for analysts and other data professionals to contribute to the dbt project, however, there are 2 key skills that they will need: SQL and git. And that leads into the final accomplishment I would like to talk about: bringing my Software Carpentries instructor experience to the City.

Teaching computational skills workshops for City workers

In grad school, I got involved with the Software Carpentries and became a certified instructor. I learned how to teach core computational skills (bash, git, SQL, python) to beginner learners in the context of also teaching reproducible research skills. I really liked the Carpentries teaching philsophy of live-coding, conscientious language, and getting learners to the point of using the technical skills as fast as possible (workshops average about 3-4 hours). Also, all of the lesson plans and content are open source, so technically anybody can teach a workshop using Carpentries material.

In 2023 I got the chance to teach a couple different Carpentries workshops. When the analysts on the team started expressing interest in having their own github repo for the growing number of projects using python rather than a dashboarding BI tool, I offered to teach the Carpentries workshop on git with some custom content tailored for the team. This ended up being folded into a larger data culture pilot program during the summer and was opened up to other City workers as well. During the latter half of that data culture pilot, I was also able to teach some material on pandas from the Carpentries python workshop.

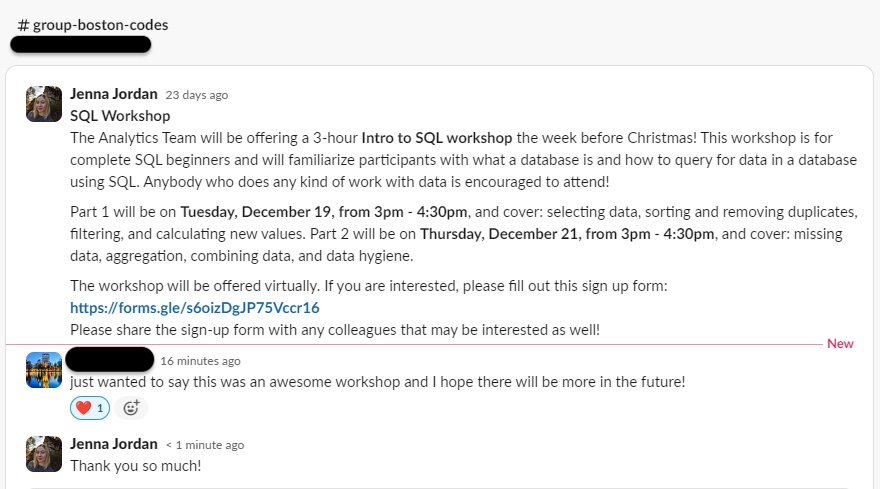

In December, I also decided to host a SQL workshop and opened it up to any city worker who might be interested. I knew that SQL skills were going to become more important for analysts across the city who may be expected to query the data warehouse in order to rebuild a dashboard in Power BI, and I also just really enjoy teaching the Carpentries SQL workshop.

One amazing outcome of these workshops? Another team at the city who used the Analytics team data warehouse and had specific subject matter expertise used the opportunity to upskill their analysts and started using a GitHub repo to store and collaboratively develop SQL queries to create tables/views that could build on each other. This is a significant and useful step forward from saving long, convoluted SQL in the BI tool, as well as making it much easier on the data engineering team to later incorporate these queries into the dbt project.

Wrapping up

This post is already longer than it needs to be, so I’m not going to spend too much time wrapping up. I will just say this: during my 2+ years at the City of Boston I was able to learn a lot by doing, I accomplished a few key things that I hope will have a lasting impact, and I met some really amazing people whom I hope to stay connected with for the long haul. There are also a lot of projects I worked on that I did not talk about in this blog post - this was primarily about the internal data engineering work I did. However, the vast majority of my time was spent on projects completed for stakeholders, who came to the Analytics team for data project help. It is not really my place to talk in detail about those projects, but I will say that I had a fantastic time contributing my expertise to their work - especially those longer, more complex projects that had a direct impact on constituent lives. I look forward to seeing what all of my former colleagues accomplish in the years to come!

~

Did you scroll directly to the bottom just get to the conclusion, and skip right over the TL;DR? Don’t worry, here it is again:

tl;dr

Maybe you don’t feel like going on a journey with me at the moment, and you just want the highlights - this section is just for you.

What I learned:

- How to work with data warehouses (ELT, workflow orchestration, flow of transformations, testing the data, etc)

- Patterns of collaboration & communication with fellow engineers (e.g. PR flow & etiquette, documenting work), analysts (e.g. division of responsibilities, data modeling), and stakeholders (e.g. requirements gathering, advocating for data engineering best practices)

- The formal process of process improvement - how to develop and communicate innovative projects that will improve daily processes

- How to start a dbt project from scratch and iteratively grow its architecture & adoption

- How to present a fairly technical data engineering process improvement project to teammates, leadership, and a wider audience

What I accomplished:

- Starting & growing the City Analytics Exchange, a casual network & meetup group of data analytics practitioners in local government

- Teaching workshops (from Software Carpentries) on core technical skills like git, SQL, and python to fellow City employees (part of a larger data culture initiative)

- Integrating dbt into the data engineering team’s tech stack, and re-organizing the data warehouse along the way

- Presenting about the dbt migration project at Coalesce 2023

- Collaborating across many teams & individuals in the department to deliver the team’s first data catalog as an official product supported by the department (SSO, boston.gov URL, data governance work initiated to support continued development)

Links to look at next:

- Blog post: Analytical Data Warehouses - an introduction

- Project page: dbt Migration at City of Boston

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: