Python can be tidy too: pandas recipes for normalizing data

Poster virtually presented at PyCon2020, accompanied by the Tidy Pandas Cookbook repo.

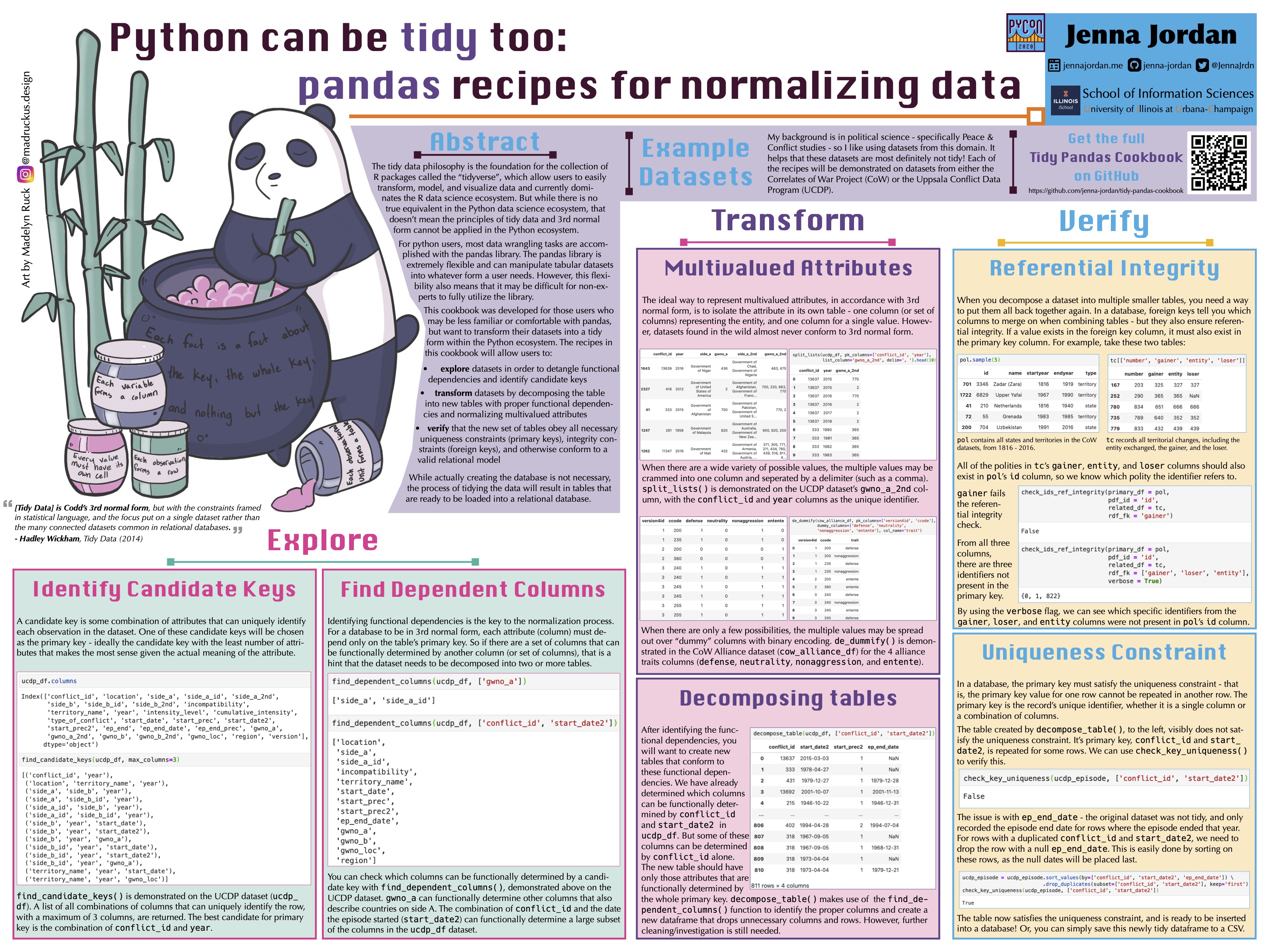

I virtually presented my poster ‘Python can be tidy too: pandas recipes for normalizing data’ at PyCon2020, which is accompanied by the Tidy Pandas Cookbook. The Tidy Pandas Cookbook contains recipes utilizing the pandas library for wrangling datasets into 3rd normal form. A selection of these recipes are demonstrated in the poster.

Please take a look at my poster for PyCon 2020, entitled “Python can be tidy too: pandas recipes for normalizing data”, here:

The poster is also available at the PyCon 2020 Online Poster Hall.

Art Credit

The adorable Tidy Panda featured on the poster was created by Madelyn Ruck. See her other creations on her Instagram page, @madruckus.design.

Tidy Pandas Cookbook

The cookbook contains recipes that utilize the pandas library to transform data into a tidy (third normal) form. Each recipe is demonstrated in a notebook with real-world messy datasets. The recipes belong to three general categories: explore, transform, and verify.

The Tidy Data Philosophy

The term “tidy data” first entered the Data Science vernacular with Hadley Wickham’s 2014 paper “Tidy Data” and accompanying R packages that would aid users in the data tidying process. However, the underlying theory behind “tidy data” is Codd’s relational model, which itself is based on first order predicate logic and the theory of relations (it’s philosophical turtles all the way down). As Wickham states in his paper, the principles of Tidy Data are those of Codd’s third normal form, reframed for statisticians.

The original 3 rules of tidy data (2014) were:

- Each variable forms a column.

- Each observation forms a row.

- Each type of observational unit forms a table.

Wickham later altered them in his 2016 book “R for Data Science” to be:

- Each variable must have its own column.

- Each observation must have its own row.

- Each value must have its own cell.

Together, these rules are equivalent to the rules for a database in Third normal form:

- All attributes are atomic (single-valued)

- Every non-key attribute is functionally dependent on the (entire) primary key

- There are no transitive dependencies - no nonprime attribute is functionally dependent on another non-prime attribute

To make some of the vocabulary discrepancies clear, attributes are equivalent to variables, which are stored in a column. Primary keys are the column, or set of columns, that act as the unique identifier for an observation, which are stored in rows. An attribute is a “prime attribute” if it is part of the primary key. Observational units are another way of saying “entities”.

Third normal form was summed up by William Kent (author of “Data & Reality”) as:

“Every fact is a fact about the key, the whole key, and nothing but the key” (… so help me Codd).

Tidy Data & R… & Python?

The tidy data philosophy is the foundation for the collection of R packages called the “tidyverse”, which allow users to easily transform, model, and visualize data. But while the tidyverse currently dominates the R data science ecosystem (although it is not without its detractors), there is not a true equivalent in the Python data science ecosystem. But that doesn’t mean that the principles of tidy data and third normal form cannot be applied in the Python ecosystem.

For python users, most data wrangling tasks are accomplished with the pandas library. Data tidying is just one of the many tasks that could be described as data wrangling… but in my opinion it is the most important. The pandas library is extremely flexible and can manipulate tabular datasets into whatever form a user needs. However, this flexibility also means that it may be difficult for non-experts to fully utilize the library.

This cookbook was developed for those users who may be less familiar or comfortable with pandas, but want to transform their datasets into a tidy form within the Python ecosystem. The recipes in this cookbook will allow users to:

- explore their datasets in order to detangle functional dependencies and identify candidate keys

- transform their datasets by decomposing the table into new tables with proper functional dependencies, creating new identifiers, separating multivalued attributes, and otherwise normalizing the dataset(s

- verify that the new set of tables obey all necessary uniqueness constraints (primary keys), integrity constraints (foreign keys), check constraints, and otherwise conform to a relational model such that it could be loaded into a database.

While actually creating the database is not necessary, the process of tidying the data will result in tables that are ready to be loaded into a relational database (and pandas’ sqlite3 API makes this last optional step easy).

The example datasets

My background is in political science - specifically Peace & Conflict studies - so I like using datasets from this domain. It helps that these datasets are most definitely not tidy! Each of the recipes will be demonstrated on datasets from the Correlates of War Project (CoW) and the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP). These datasets will be used in the Jupyter notebooks that demonstrate how each function can be used on a real-world messy dataset.

References

Wickham, H. (2014). Tidy data. Journal of Statistical Software, 59(10), 1-23.

Wickham, H., & Grolemund, G. (2016). R for data science: import, tidy, transform, visualize, and model data. O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Kent, W. (1983). A simple guide to five normal forms in relational database theory. Communications of the ACM, 26(2), 120-125.

Codd, E. F. (1972). Further normalization of the data base relational model. Data Base Systems.

Kent, W. (2012). Data and Reality: A Timeless Perspective on Perceiving and Managing Information. Technics publications.